Good Climate News this Week: Rules to Cut Pollution, an Offshore Wind Transmission Plan, Emissions Reduction in the EU, and More!

Apr 15, 2024

*The opinions presented in this article are Cam Juarez’s own and do not represent positions or policies of the National Park Service*

“My role in the Park Service is to find ways to empower gente, to find ways to take public lands and historical narratives back.” For Cam Juarez, a National Park Ranger in Arizona’s Saguaro National Park, getting historically excluded communities outdoors and into public lands is paramount to his mission. He strives not only to preserve its rich history, but also to preserve the stories of heritage similar to his own.

Cam introduces himself as the first-generation son of Mexican immigrants from a pueblito in Michoacán, Mexico. “A lot of my heritage has not been shared with me – pero estoy aprendiendo,” he said while sharing his pride of his family’s Indigenous Mixtec roots.

Cam’s drive to further understand how his personal identity shapes his experiences in the outdoors also drives him to amplify the stories of people historically excluded from public lands. “There’s a lot of history, pero like with any family, we all have a lot of backstories that we are sometimes ashamed of and that we don’t like to talk about.”

Cam reminds us that “up until 1964, it was difficult for a lot of people of color to exist in public lands. There were segregated states where black people weren’t welcomed on public lands,” he highlights, adding that “much of our nation’s ‘public lands’ were pilfered from First Nation and Indigenous peoples during treaty negotiations, and our public lands represent only a small portion of the land that was forcibly taken from Indigenous peoples. We are always, always on native land.” We must learn to acknowledge our challenging past, and heal through collaboration and meaningful partnerships with Indigenous communities.

When he’s out in the field, Cam is deeply conscious that, as a representative of the Park Service, he has a profound effect on whether or not visitors feel welcome to explore spaces that have historically excluded them.

“As a professional series park ranger, I’m supposed to be in uniform most of the time. But I’m not,” he says. “I made that agreement with my jefas, because sometimes for our gente here on the borderlands, there is historical trauma in a uniform. Personally, I remember a uniform taking my Jefito away in handcuffs. I remember a uniform escorting him behind bars…The first time I saw snow, and the beauty of wilderness, it was in a facility on prison grounds where my dad could share time with his family while he paid his debt to society. Ultimately, it was uniforms that deported my father back to Mexico. And it’s uniforms that keep him and other dads out of the United States.”

In recognizing barriers to connecting with communities, Cam hopes to educate not just park staff and public land stakeholders. He also wants to help inform National Park Service leadership, our elected officials, and park visitors about the advantages of engaging historically excluded community members in efforts to conserve public lands and spend time outdoors. While he knows we have a long way to go, he is optimistic of the progress already made. There are lots of people in the Park Service looking to help underserved communities, he says. “This July I turn 50 — and in the last 30 years I have seen so many things begin to change. ”

Research on social trends on public lands reveal an increase in the number of Latinx people recreating outdoors and using public spaces over the last ten years. Latinx communities also disproportionately experience health problems caused by deeply entrenched social inequities and environmental racism, so encouraging engagement with the outdoors is especially important. Today, when Cam goes to municipal parks, he remarks, smiling, “you see the dudes’ barriguitas in their barrio walking clubs. Sometimes you see the señoras or señores by themselves, just walking – maybe some old-school headphones on their ears – and they are walking the trail around the park because they know that they have to lose some weight, or lower their cholesterol, or they have to get their blood sugar down.”

For Cam, again, it’s personal: “I’m a Type 2 Diabetic and heart patient. I have to get exercise. Si no, me muero! And that’s part of our cultura, connecting to the land to heal ourselves. So public lands to me means much more than just Saguaro National Park, the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, or Yosemite. It means getting outdoors, and it means community. It also means traditions and sharing experiences across muchas generaciones.”

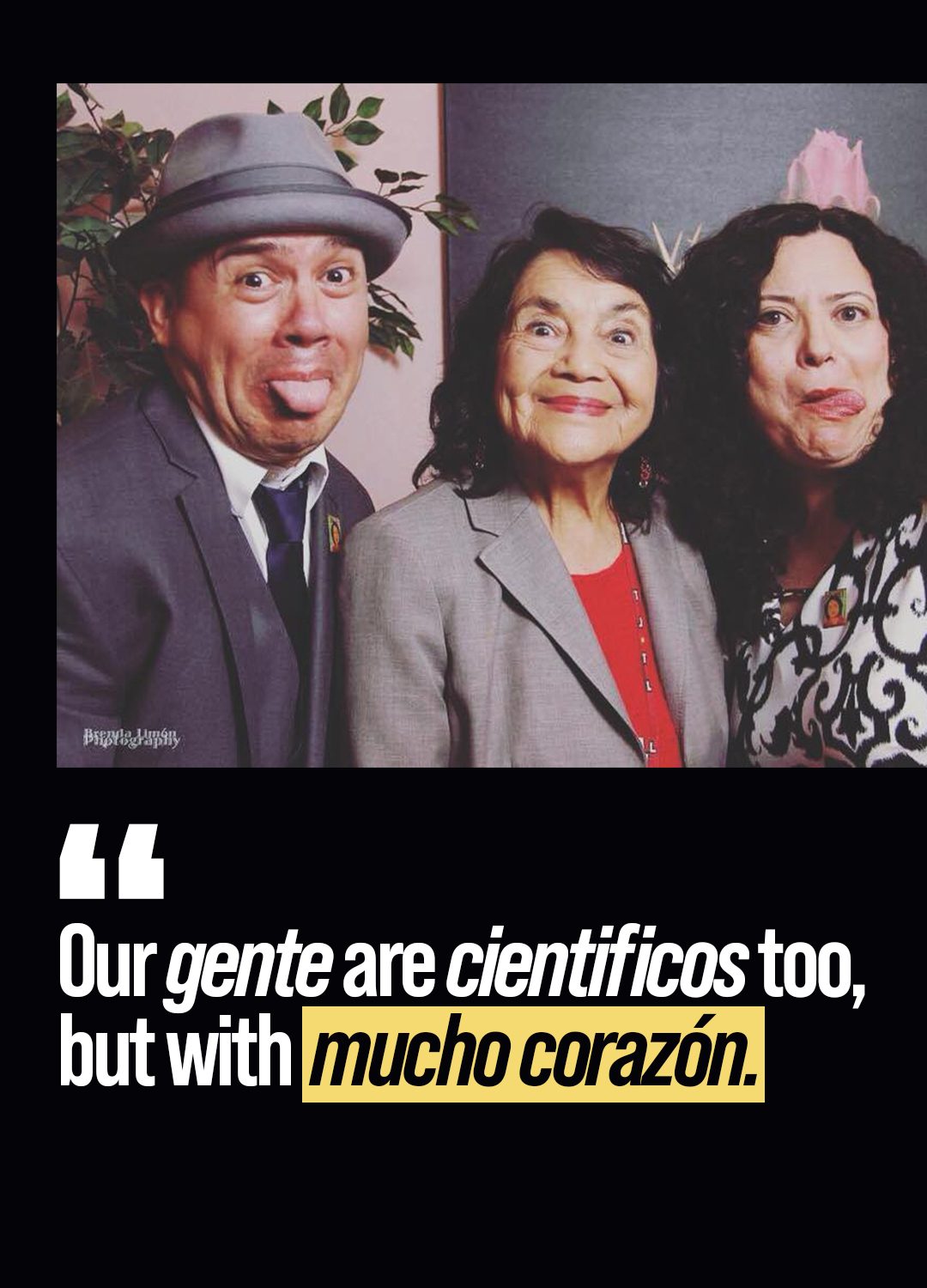

Cam says that his position as the Community Engagement Coordinator is the result of the Park Service recognizing that the Latinx community is a growing demographic with increasing economic and political power. He also acknowledges that more young people are entering the science fields and are career focused on environmental justice. He reminds us that “Our gente are cientificos too, but with mucho corazón.” Cam hopes to be a part of guiding underrepresented communities to be a strong voice for protecting public lands. “If we don’t connect with public lands, if we don’t fall in love with them and want to protect them, then we’re not going to vote for the right people that are going to want to protect them.”

The energy Cam pulls from to work towards building this community power comes in part from an Indigenous story that his second grade teacher, who was Navajo or Diné, told him as a young kid. Cam grew up with a physical disability caused by his mother’s exposure to herbicides while pregnant and working as a farm worker in California. He sat down with his teacher one day after getting in trouble for lashing out at his bullies.

Cam recalls Mrs. Steelings telling him,“In my culture, a lot of birds, animals, and insects are sacred. One insect that is kind of a trickster in our community is the honeybee. The honeybee is an awkward creature, because its body isn’t really designed to do what it does with such small wings – it has a really large body, and small wings. But somehow, it still does what it needs to do.”

“The reason why the honey bee continues to do what it does is because it doesn’t care that it’s got small wings. It still has an important job to do, so it just keeps doing what it needs to do. No one is telling the honey bee that it can’t do these things. If the honeybee stops doing what it does, it’s only because the honey bee stopped itself.” She paused. “So that’s you, you’re the honey bee. You need to forget what people think of you and you need to start doing what you need to do.”

So that’s what Cam is doing – doing what he needs to do to increase representation on public lands, and urging others to do the same. His advice? “Start your own group. We can’t lowrider in the wilderness, but we can certainly go for a slow stroll out there. Do what you do, have fun with it, and pass it down to your familias and your friends and your vecinos. And if resources, accommodations or amenities are needed, ask for them, demand them if need be. And find like-minded partners and advocates. But most importantly, just get them out there, because that’s how we’re going to control our health – whether it is our mental, our physical, or even our spiritual health. Let’s get out there and do that, ¡por favor!”

Join us! If you would like to support Chispa Arizona and stay up to date on ways to get involved, become a Chispa Arizona member.

Header image of Saguaro National Park by Joe Parks, presented without alteration and licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.